Summary

- The interaction between ancient Egypt and Greece, though geographically distant, was one of the most profound cultural exchanges in the ancient world.

- Spanning centuries through trade, conquest, and intellectual curiosity, Egypt greatly influenced Greek religion, art, architecture, philosophy, and science.

- This influence can be seen in various aspects such as shared religious deities like Isis and Demeter, similar creation myths, Egyptian artistic motifs in Greek sculpture, the architectural adoption of Egyptian columns, and the transmission of mathematical, astronomical, and medical knowledge.

- The Greek colony of Naucratis in Egypt acted as a hub for cultural exchange.

- The influence also extended to coinage, where hybrid deities like Serapis symbolized the fusion of Egyptian and Greek traditions.

- This cultural synthesis continued to shape the Hellenistic period and left a lasting legacy in Western thought and heritage.

How Did Egypt Influence the Culture of Ancient Greece? is a powerful question that shows the strong connection between the ancient cultures of Egypt and Greece. Although geographically distant, the interaction between ancient Egypt and Greece was one of the most influential cultural exchanges in the ancient world.

Spanning centuries, this relationship was driven by trade, conquest, and intellectual curiosity. Egypt’s long-established civilization deeply shaped Greek religion, art, architecture, philosophy, and science. This article delves deeper into how the Ancient Egyptian Civilization influenced ancient Greek culture, providing historical facts, data, and examples to illustrate the depth of this cross-cultural interaction.

Religious Parallels: Shared Deities and Myths of Both Civilizations

Cosmogonies and Creation Myths: Similarities in Origin Stories

Both Egyptian and Greek cultures developed detailed creation myths to explain the origins of the world, and striking similarities can be found between their respective cosmogonies.

Egyptian Cosmogony: In the Hermopolitan cosmogony (around 2000 BCE), the Egyptian creation tale starts with Atum who was the primordial god that created the world from the primordial waters of Nun. Atum’s offspring, Shu (air) and Tefnut (moisture), created Geb (earth) and Nut (sky), representing a familiar cycle of elements. These deities are in line with Egypt’s belief in the cyclical nature of creation and destruction, linked to natural forces.

Greek Cosmogony: In Hesiod’s Theogony (circa 700 BCE), the first gods—Chaos, Gaia (Earth), and Tartarus—emerge from the void. This early concept of chaos leading to the formation of the earth and sky mirrors the Egyptian cosmogony’s elemental focus. Both mythologies view the world as emerging from a primordial state of disorder, followed by the birth of deities representing natural forces.

Both traditions share the idea of the world’s creation from chaos, suggesting that early Greek thought may have been influenced by Egyptian models or traditions indirectly passed through the eastern Mediterranean.

Isis and Demeter: Parallels of Fertility and Afterlife

The Egyptian goddess Isis and the Greek goddess Demeter share significant parallels, particularly in their roles as protectors of fertility and the afterlife.

Isis: As one of Egypt’s most important deities, Isis was associated with healing, fertility, and the resurrection of the dead, especially in the myth of Osiris, where she resurrects her brother-husband, Osiris, through magical rituals. She was worshipped across the Roman Empire, including in Greece, and her cult flourished especially after Alexander the Great’s conquests.

Demeter: Demeter, the Greek goddess of agriculture, also presided over fertility and the harvest. Like Isis, she is deeply connected with the Ancient Egyptian afterlife, especially through the myth of her daughter Persephone, whose annual descent into the Underworld and return symbolizes cycles of death and rebirth.

The Mysteries of Isis, practiced widely in the Hellenistic world, closely resembled the Eleusinian Mysteries in Greece, where initiates learned secret rituals that promised a blessed afterlife, reflecting Egyptian religious influence on Greek ritual practices.

Artistic Exchanges With the Egyptian Motifs in Greek Art

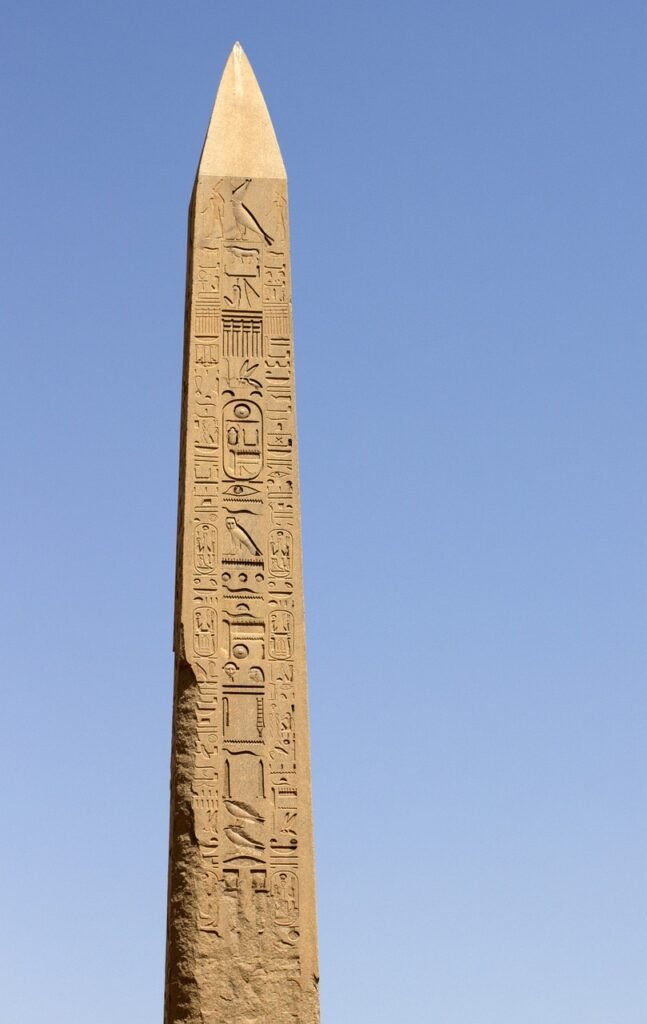

Sculptural Techniques and Styles: Influence of Egyptian Form

Greek sculpture, particularly in the Archaic period (circa 600–480 BCE), reveals clear Egyptian influences, especially in early statues of young men called kouroi (plural of kouros).

Egyptian Influence: Egyptian statues of pharaohs, such as those found in the tombs of the Old Kingdom (circa 2686–2181 BCE), often featured a rigid, frontal pose, with one foot forward and the figure’s arms at the sides. This pose, symbolizing power and stability, was adopted by Greek sculptors in the creation of their kouros figures.

Greek Adaptation: The Greeks began to refine this style by introducing greater anatomical detail and incorporating a more dynamic stance. For example, the early Greek statue of Kroisos (circa 530 BCE) features a more naturalistic portrayal of the human body but still follows the Egyptian tradition of frontal positioning. This fusion of Egyptian rigidity with Greek anatomical study laid the foundation for the later fluidity and movement found in Classical Greek sculpture.

Iconography and Symbolism: Egyptian Motifs in Greek Art

Egyptian symbolism made its way into Greek art through cultural exchange, especially after Egypt became a key trade partner.

Lotus and Sphinx: The lotus flower, a symbol of rebirth and creation in Egypt, appears frequently in Greek art, particularly in pottery and architectural decoration. Similarly, the sphinx, often used in Egyptian temples to guard sacred spaces, was adopted by Greek artists, especially during the Hellenistic period (323–30 BCE). The Greek sphinx, though typically depicted with a human face, retained its association with mysticism and divine protection.

The Dendera Zodiac: The Dendera Zodiac (c. 50 BCE), an Egyptian star chart, influenced Greek astrology. The twelve signs of the zodiac in Greek tradition closely parallel the Egyptian constellations, with the zodiac system itself originating from Babylonian and Egyptian astronomical observations.

Architectural Inspirations Between the Two Civilizations From Columns to Temples

Columnar Designs: Egyptian Influence on Greek Architecture

The Greek column owes much to Egyptian architectural developments, particularly in the use of monumental columns.

Lotus and Papyrus Capitals: Egyptian columns were often topped with capitals shaped like lotus flowers or papyrus plants, symbols of the Nile River and fertility. These forms heavily influenced early Greek columns, such as those in the Doric and Ionic orders, which included ornamental elements inspired by Egyptian designs. The Greek Doric order, which became the standard in classical architecture, was simpler than its Egyptian counterparts but retained a sense of monumental grandeur.

Greek Adaptation: The Greeks adopted and refined the use of columns in their temples. The Temple of Hera at Olympia (circa 600 BCE) features the use of columns with more refined proportions, setting the stage for the more iconic Greek temples such as the Parthenon (447–432 BCE).

Temple Layouts and Alignments: Egyptian Influence on Greek Temples

The layout and alignment of Greek temples show evidence of Egyptian influence, especially in the use of astronomical alignments.

Astronomical Alignment: Egyptian temples were meticulously aligned with celestial bodies to mark significant events like solstices and equinoxes. Similarly, Greek temples like the Temple of Amun-Ra in Delphi (circa 6th century BCE) exhibit similar celestial alignments, reflecting the influence of Egyptian temple planning.

Egyptian Temple Designs: The Hellenistic period saw an even greater blending of Greek and Egyptian architectural styles, particularly in the city of Alexandria, where Greek temples were often influenced by Egyptian forms and rituals, like the Serapeum of Alexandria (c. 300 BCE).

Philosophical and Scientific Transmissions Between Ancient Egypt and Greece

Mathematics and Geometry: Egyptian Knowledge to Greek Philosophers

Egypt was a leader in mathematics and geometry, especially with its monumental architecture and land surveying practices.

Pythagoras: The Greek philosopher Pythagoras (circa 570–495 BCE) is said to have studied in Egypt, where he encountered advanced principles of Ancient Egyptian mathematics used in the construction of the pyramids. The Pythagorean theorem, crucial to Greek geometry, likely drew on Egyptian methods for solving geometric problems in construction.

Plato: Plato (circa 428–348 BCE) was also influenced by Egyptian teachings, as evidenced by his references to Egyptian wisdom in his dialogues. He also mentions in his work Phaedrus that the Egyptian god Thoth invented writing, further acknowledging Egypt’s contribution to Greek intellectual traditions.

Trade and Cultural Interactions: The Role of the Greek Colony of Naucratis in Egypt

Naucratis as a Cultural Hub

The Greek colony of Naucratis in Egypt, founded around 630 BCE, served as a crucial center for Ancient Egyptian trade and cultural exchange with Greece.

Cultural Syncretism: Naucratis was the first officially recognized Greek colony in Egypt, and it attracted Greek traders, soldiers, and artists. Artifacts discovered in the area—such as Greek pottery with Egyptian motifs—demonstrate how Greek artists were exposed to and inspired by Egyptian art, architecture, and religious practices.

Historical Significance: Archaeological evidence from Naucratis, including inscriptions and artwork, reveals how Egyptian influences permeated Greek culture during the Archaic and Classical periods (circa 600 BCE – 323 BCE).

Symbolism and Numismatics: The African Head on Greek Coinage

Coin Imagery and Cultural Significance

The depiction of African features on Greek coins serves as an enduring testament to the cultural, political, and economic ties between Greece and Egypt. Both Greek and Ancient Egyptian Coins were not merely tools for commerce; they were carriers of powerful symbols reflecting the interconnectedness of the ancient Mediterranean world.

African Imagery on Coins: During the Ptolemaic era (305–30 BCE), coins minted in Alexandria frequently bore imagery that linked Greek and Egyptian traditions. Among these, African heads appeared as representations of Egypt or the broader African continent. This was especially prevalent during the reign of Ptolemy I Soter, who used these symbols to communicate his legitimacy as a ruler of both Greek and Egyptian peoples.

Serapis and Hybrid Deities: Coinage often featured hybrid Greco-Egyptian deities such as Serapis, a syncretic god combining aspects of Osiris, Apis, and Hades. The use of such imagery symbolized the blending of Greek and Egyptian religious practices, emphasizing unity under Ptolemaic rule.

Economic and Political Implications Between Greece and Egypt

The presence of African heads and other Egyptian symbols on Greek coins underscores the strategic importance of Egypt in Greek economic and political life.

Economic Significance: As the granary of the ancient world, the economy of Ancient Egypt was critical to the Hellenistic economy. Greek coins featuring Egyptian motifs highlighted the wealth and resources that Egypt contributed to the Greek world, especially its agricultural abundance and trade goods like papyrus, grain, and gold.

Political Messaging: Coinage served as a propaganda tool to assert the Ptolemaic dynasty’s authority over Egypt. By combining Greek and Egyptian symbols, the Ptolemies demonstrated their dual identity as heirs of Alexander the Great and legitimate pharaohs of Egypt, ensuring loyalty among diverse populations.

Cultural Impact Between Greece and Egypt

The hybrid imagery on these coins provides insights into how Greeks viewed Egypt and Africa. Far from being seen as alien, Egypt was respected as a land of ancient wisdom and fertility. The depiction of African heads was not merely a reflection of geographic boundaries but an acknowledgment of Egypt’s vital cultural and economic role in the Greek world.

The Influence of Egyptian Science and Medicine on Greek Thought

Astronomy and Calendar Systems

Egyptian contributions to astronomy and calendar systems were pivotal in shaping Greek scientific thought.

Egyptian Astronomical Knowledge: Ancient Egyptians were advanced in tracking celestial bodies, especially the star Sirius (the Dog Star), which they used to predict the annual flooding of the Nile River. This deep understanding of celestial movements directly influenced the Greek approach to astronomy.

The Dendera Zodiac (c. 50 BCE), an Egyptian star chart discovered in the Temple of Hathor at Dendera, is a prime example of Egyptian precision in astronomy. Greek astronomers, such as Hipparchus (c. 190–120 BCE), are believed to have had access to Egyptian astronomical data, which contributed to the development of their own systems.

Calendar Systems: The Egyptians were also pioneers in the development of a solar calendar, with 365 days in a year. The Greeks initially used a lunar calendar, but the Egyptian solar calendar was later adopted by the Greeks, especially after Alexander the Great’s conquest of Egypt. This Egyptian Calendar influence can be seen in the Alexandrian calendar, which played a central role in the later development of the Julian calendar.

Egyptian Medicine: Knowledge Transfer to Greek Physicians

The transmission of Egyptian medical knowledge to Greece is often attributed to the influence of Egyptian priests and scholars, who were highly regarded as medical experts.

Greek Physicians in Egypt: Renowned Greek physicians, such as Hippocrates (c. 460–370 BCE) and Herophilus (c. 335–280 BCE), are believed to have traveled to Egypt to study medicine. Hippocrates, often referred to as the “Father of Medicine,” is said to have visited Egypt, where he learned about Egyptian medical practices, including the use of herbs, surgical techniques, and anatomy.

Egyptian embalming practices, which required detailed knowledge of human anatomy, were also instrumental in shaping Greek understanding of the human body.

Greek Adaptation: The Greeks adopted many Egyptian medicinal practices, especially in the realms of surgical procedures and herbal remedies. Egyptian medicine’s emphasis on hygiene, diagnosis, and practical treatment became foundational in the development of Greek medical theory.

Ptolemaic Alexandria was a center for medical knowledge, and the Library of Alexandria housed extensive medical texts that incorporated both Egyptian and Greek contributions to the field.

Political and Economic Influences: Greek Expansion and Egyptian Legacy

The Role of Alexandria as a Center of Power and Culture

The city of Alexandria, founded by Alexander the Great in 331 BCE, became one of the most important cultural and intellectual hubs in the ancient world, merging Greek and Egyptian elements.

Ptolemaic Rule: After Alexander’s death in 323 BCE, his general Ptolemy I Soter took control of Egypt, establishing the Ptolemaic dynasty, which ruled Egypt until the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BCE. Under Ptolemaic rule, Alexandria became a vital center for both Greek and Egyptian culture.

The Greeks introduced their own governmental structures, military systems, and philosophy, while Egypt’s rich religious traditions, monumental architecture, and scientific knowledge greatly influenced Ptolemaic governance and Egyptian society.

Economic Significance: Alexandria’s strategic location along the Mediterranean trade routes made it an economic powerhouse, linking Greece, Egypt, and the wider Mediterranean world. The Ptolemaic dynasty heavily utilized Egypt’s vast resources, particularly in grain production, to fund their rule and maintain economic stability.

The city’s Great Library and Lighthouse of Alexandria, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, attracted scholars, philosophers, and traders from all over the world.

Greek-Egyptian Numismatics: Reflection of Political Dominance

Coins minted during the Ptolemaic era often featured Greek and Egyptian iconography, symbolizing the merging of two distinct cultural traditions under a single political entity.

Ptolemaic Coinage: The coins of Ptolemy I (323–283 BCE) and his successors depicted both Greek deities, such as Zeus, and Egyptian symbols, including the image of the god Serapis, a syncretic figure combining aspects of Osiris and Apis with the Greek god Hades.

These coins were a reflection of the political unity between the two civilizations, blending Greek and Egyptian cultural elements to legitimize Ptolemaic rule.

Cultural Integration: The use of Egyptian deities on Greek coins, alongside Greek inscriptions and designs, reveals the political and cultural blending that occurred under the Ptolemaic dynasty.

The coinage served as a powerful tool for both economic transactions and cultural representation, symbolizing the dual heritage of the Ptolemaic rulers.

Literary and Intellectual Influences: Greek Writers and Egyptian Lore

The Influence of Egyptian Literature on Greek Writers

Greek writers and philosophers were profoundly influenced by Egyptian religious texts, myths, and wisdom. The proximity of Greek colonies like Naucratis and the intellectual cross-pollination facilitated the transfer of Egyptian literary traditions to Greek authors.

Herodotus: The Greek historian Herodotus (c. 484–425 BCE), often called the “Father of History,” visited Egypt during his travels in the 5th century BCE. In his famous work, Histories, Herodotus provided detailed accounts of Ancient Egyptian religion, customs, and history, many of which would have been unknown to his Greek audience. His admiration for Egypt’s ancient civilization is evident in his writings, where he frequently references Egypt as a source of wisdom and knowledge.

Plutarch: The Greek philosopher and historian Plutarch (c. 46–120 CE) also recognized the influence of Egyptian religious thought on Greek intellectual traditions. In his work Moralia, Plutarch discusses Egyptian deities like Isis and Osiris, noting their influence on Greek religious practices. He also explored the mystical aspects of Egyptian philosophy, which inspired later Greek philosophers.

Greek Philosophy and Egyptian Mysticism: Greek philosophers, including Plato, often drew on Egyptian wisdom in shaping their metaphysical ideas. Plato’s dialogues, particularly Timaeus, reflect Egyptian influence, with their focus on cosmology, the soul, and the divine order of the universe. The Egyptian concept of the soul’s immortality and the importance of moral purity were echoed in Greek philosophical traditions, especially through figures like Pythagoras and Plato.