Summary

- This article explores the fascinating world of mythical creatures and monsters in ancient Egyptian mythology.

- From fearsome beings like Ammit and Apep, who devoured souls and battled gods, to sacred symbols like Bennu, the phoenix-like bird of creation, and Khepri, the scarab of rebirth, each creature represented cosmic forces, divine will, and the dual nature of life and death.

- Many were hybrid animals blending lion, crocodile, hawk, or serpent traits, reflecting Egypt’s spiritual and environmental landscape.

- Everyone will discover creatures that guarded the underworld, punished the wicked, and guided the sun across the sky.

- Legends like El Naddaha, the Nile’s siren, or the enigmatic Set animal also show how myth blended with daily life and moral lessons.

- These beings were central to Egyptian religion, funerary practices, and royal symbolism, leaving a lasting legacy in both history and global mythologies.

The ancient Egyptian mythical creatures and monsters were the products of the vivid and complex imagination of the ancient Egyptians, who sought to explain the meaning behind the forces that governed them and their surroundings. Ancient Egyptian mythology is filled with many gods and goddesses who are each responsible for an aspect of reality, like the seasonal flooding, the cyclic pattern of the sun & stars, the coming of death, the birth of life, chaos, harmony, and many more. Each idea transformed into a celestial being to took the shape of a physical object.

The unique environment of Egypt, which was composed of the fertile Nile River delta, which was surrounded by desert and arid lands, which was populated by epic fringe groups of nomads and raiders. These groups and the ancient Egyptian animals of the desert, which were believed to form the outer realms and the harmony & balance of the ancient Egyptian people and their society, played a dual key role in shaping the narrative of most of the mythological monsters and creatures. In this article, we will uncover the most legendary Ancient Egyptian Mythical Creatures and Monsters, which are:

Aani – The Sacred Baboon of Thoth and Divine Judgment

The Cynocephalus Baboon, known as Aani, held special reverence in the ancient Egyptian religion and the total belief system as it was associated with the deity Thoth. The term “Aani” referred to the dog-headed ape and was employed to depict the sacred connection between this creature and the god Thoth. The Book of the Dead of Ani was a highly important funerary text that offered the needed instructions and spells to guide the deceased through the afterlife and provide the soul with the skills to conquer many trials and challenges to arrive at the realm of Osiris to achieve eternal life.

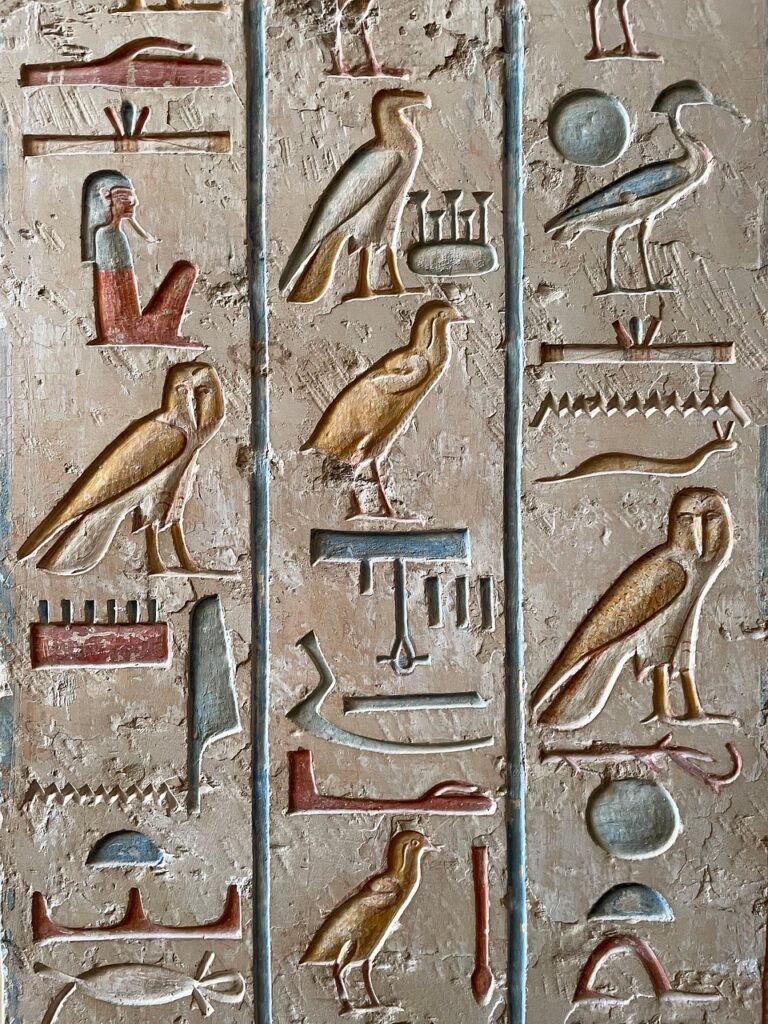

The Egyptian hieroglyph for “baboon” is represented as jꜥnꜥ. This hieroglyphic word, found in existing literature on approximately forty occasions, directly denotes the baboon species itself. Numerous Ancient Egyptian gods were linked to the baboon in various ways or could manifest with baboon-like attributes. Among these deities were:

- Hapy was a guardian of the canopic jar that held the lungs post-embalming.

- Khonsu was a deity referenced as the “eater of hearts” in the Pyramid Texts.

- Thoth was a god associated with reason and writing.

An 18th Dynasty text states, “And thus came into existence the Baboon of Thoth.” The depiction of these animals through iconography did not signify that the ancient Egyptians perceived them as divine beings themselves. Instead, these animals were utilized as icons or sizable hieroglyphs to symbolize specific gods.

Abtu – The Celestial Fish of the West and Guide of Ra

Abtu is known as both the designation for a revered fish and the name of the city of Abydos, where Osiris and early Egyptian rulers found their resting place. Abtu’s name also graced the city of Abydos, a sacred place of burial for revered figures such as Osiris and early rulers of Egypt. The fusion of these meanings and associations highlights Abtu’s intricate significance within Egyptian astronomy, cosmology, and symbolism. The term “Abtu” originally conveyed the concept of the western or westerly direction.

This interpretation evolved to represent the location where the sun’s daily journey through the sky concludes, marking the point of the sun’s daily demise and passage into the shadowy underworld, particularly pertinent in ancient Egyptian beliefs. Many believe that the Abtu was a type of edible species of tilapia which was used as a holistic ingredient for many medicines

Within the realm of myth, Abtu was recognized as an attendant to the celestial boat of Ra, accompanying it on its celestial voyage across the sky at the break of dawn. This portrayal emphasized Abtu’s role as a key element in the cycle of the sun’s passage and its subsequent rejuvenation. The mythical stories of Abtu and Anet were responsible for guiding the royal solar barge to the sun god Ra and also were responsible for the reconnaissance and protection for the barge as they sailed in front of the ship through the primordial waters of the Nun which battling Apep.

Abtu was responsible for alerting the gods on the solar boat of the arrival of the monsters of darkness, while Anet was tasked with the defense of the vessel itself. It was seen as a sacred fish that can be traced back to the words of “A Hymn of Praise to Ra When He Rises in the Eastern Part of Heaven,” which implores, “Let me behold the Abtu Fish at his season.”

Abtu was referred to as the direction of the west, which was known to be the ultimate direction of Ra. Moreover, the goddess Isis assumed the form of Abtu, perhaps bestowing upon the creature its sacred significance. In the city of Oxyrhynchus, Isis was known as the ‘Abtu, Great Fish of the Abyss. The veneration of the fish extended its influence across various regions of Egypt.

Ammit – The Devourer of Souls and Guardian of Moral Truth

Ammit was known as the “Devourer of the Dead” or “Swallower of the Dead,” who was an ancient Egyptian mythical creature that can be seen as an ancient Egyptian version of a chimera. This fearsome being possessed the forequarters of a lion, a hippopotamus’s hindquarters, and a crocodile’s head, symbolizing the most formidable “man-eating” animals known to the ancient Egyptians. In different versions of the Book of the Dead, Ammit was portrayed with a crocodile head, a dog body, and other combinations.

In Egyptian religion, Ammit held a significant role in the funerary ritual known as the Judgment of the Dead. The term “Ammit” translates to “devourer of the dead,” emphasizing its role in the afterlife. This creature was not worshiped like other deities but was rather feared and considered a guardian demon. Its unique appearance, combining the traits of three deadly predators, was intended to be recognizable to the deceased souls it encountered in the afterlife.

Ammit played a pivotal role during the Judgment of the Dead in the Hall of Truth, as in this process, the heart of the deceased was weighed against the feather of Ma’at, symbolizing truth and balance. If the heart was lighter than the feather, the deceased was considered pure and granted passage to the afterlife. However, if the heart were heavier, Ammit would consume it, leading to the soul’s eternal unrest and second death.

Ammit’s imagery evolved, with depictions showing variations in its appearance. Its presence near the scales of judgment symbolized the crucial moment of reckoning for the deceased. Ammit’s role was to serve as a stark reminder of the consequences of a life lived without adherence to the principles of truth and balance. Through its representation in funerary texts and various examples of ancient Egyptian art, Ammit underscored the importance of leading a just and virtuous life to secure a favorable judgment in the afterlife.

Apep – The Serpent of Chaos and Eternal Enemy of Ra

Apep, also known as Apepi or Apophis, was a prominent deity in ancient Egyptian mythology symbolizing darkness and disorder. Apep stood in opposition to light and Ma’at, which represented order and truth, and became arch-nemesis through the history of ancient Egyptian religion and mythology. This colossal serpent was considered the enemy of Ra, the solar deity and bringer of light.

Apep’s depictions included a giant evil serpent, often associated with chaos, disorder, and malevolence. Apep’s significance highlighted the eternal struggle between order and chaos in Egyptian cosmology, with Ra’s triumph over Apep reinforcing the importance of maintaining cosmic harmony and truth.

Apep’s origin myths varied, but he was typically believed to have existed from the primordial waters of Nu, embodying the chaos that predates creation. Apep engaged in battles with Ra, the sun god, depicted in various locations such as the underworld and the horizon. Ra’s victory over Apep was essential for the continuation of order in the world. Rituals and prayers performed by Egyptian priests and worshippers aimed to protect Ra and maintain cosmic balance. Many believe that Apep was conceived from the umbilical cord of Ra at the time of his birth, which symbolizes their eternal struggle as the ultimate representation between light and darkness.

During the 14th dynasty (1725 – 1650 BC), Apep was honored and ever worshiped as a dark entity, but in the New Kingdom (1570 – 1050 BC), Apep was pained as a gigantic demon snake that became a dark adversary of the bright god Ra. Apep’s worship involved rituals to banish chaos, such as the creation and burning of an effigy representing Apep. The “Books of Overthrowing Apep” provided instructions for these rituals, which included symbolic acts like spitting on, mutilating, and burning the effigy. The dead were also protected from Apep, as they were buried with spells to counter his influence and ensure a safe passage to the afterlife.

Bennu – The Phoenix of Creation and Symbol of Rebirth

Bennu was an ancient Egyptian deity, was closely tied to the concepts of the Sun, creation, and rebirth. This deity is considered a potential precursor to the phoenix legends of Greek mythology. In Egyptian mythology, Bennu was believed to be self-created and played a role in the world’s creation. It was associated with Ra, the Sun god, and Atum, embodying creative forces. The word bennu is derived from an ancient Egyptian verb “Wbn,” which means “to rise” or “to shine.”

Bennu was depicted as a giant serpent or, in New Kingdom artwork, as a large grey heron wearing a royal double crown known as Atef Pschent. It was often shown perched on a benben stone or a willow tree, symbolizing its connection to Ra and Osiris, respectively. Bennu’s titles included “He Who Came Into Being by Himself” and “Lord of Jubilees,” emphasizing its cyclical nature akin to the sun’s renewal. Bennu’s significance was further highlighted by its resemblance to a giant heron species discovered in the United Arab Emirates, potentially serving as the inspiration for its depiction. This heron, known as the Bennu heron, shared many attributes with the deity.

The connection between Bennu and the Greek phoenix is evident. Greek historian Herodotus described the phoenix as a bird with a similar lifespan, resurrection, and association with the sun, closely resembling Bennu’s attributes. While the Greek phoenix’s fiery rebirth is a later development, the potential link between “Bennu” and “phoenix” suggests a shared mythological origin.

Bennu’s origin can be traced to the creation myth from the golden city of Heliopolis, where the Bennu rose from the dark primordial waters of Nun, then the bird made the call for the creation of the world. In other legends, Bennu represents the soul of Ra that united with Atun to make an incredible life force, which created the world.

Although Bennu’s rebirth and sun symbolism parallel the phoenix’s attributes, Egyptian sources do not explicitly mention Bennu’s death. This connection provides insight into the cross-cultural exchange of mythological concepts and the enduring appeal of themes related to creation, renewal, and the sun across different civilizations.

El Naddaha – The Enchantress of the Nile and Voice of Doom

En-Naddāha is like a mixture between the little mermaid and the Greek siren (Celtic Banshee) that took the shape of an Egyptian legend dating to more than 5000 years about a female spirit, resembling a naiad, that lures men to the Nile, potentially leading to their demise. This tale is most prevalent in rural areas of both Lower and Upper Egypt, near the Nile and its waterways. The legend is less widespread in urban regions today but remains known among the youth and persists in rural communities.

The story involves En-Naddaha, who is a captivating mermaid woman who unexpectedly appears to men near the Nile or its canals at night. One man becomes entranced and obeys her hypnotic voice, while his companion tries to rescue him. The unaffected man eventually snaps the entranced man out of his spell, and they flee, still hearing her echoing voice. En-Naddaha’s beauty is described as a tall and slender spirit, often wearing a semi-transparent dress.

She sometimes calls men from their homes along the riverbanks, and those called are believed to be doomed, potentially drowned in the Nile. Although there are no recorded instances of men being devoured by her, the legend suggests that she may consume or drag her victims into the water. The legend also includes a belief that preventing the called man from reaching En-Naddaha may result in the preventer being the next target.

Griffin – The Fiery Tearer and Guardian of Royal Power

The griffin is one of the most recognized mythical creatures in the world that can be seen in various ancient civilizations and cultures like Egypt, Persia, Assyria, and Greece. Griffin was highly symbolic in Egyptian society without really having any story behind it, like the rest of the creatures. It was attributed a descriptive name meaning “Tearer[-in-pieces],” as seen inscribed on a griffin depiction discovered in a tomb at Deir El Bersha. Another name signifying “fiery one” has been found at Beni Hasan.

The term “Tearer” isn’t exclusively linked to the griffin, which has also been used for the god Osiris in other contexts. Depictions of griffin-like creatures were depicted as having a beaked head and four legs that can be traced back to Ancient Egyptian art before 3000 BC.

The earliest known representation of a griffin-like entity in Egypt can be found on a relief carving on Hierakonpolis’s cosmetic palette, often referred to as the “Two Dog Palette,” dating back all the way to the Early Dynastic Period (3300–3100 BC), also the tomb of Mereret which date to the 19th century BC hold Egyptian griffins depicated across the walls trampling enemies beneath their feet’s by the pharaoh himself.

Hieracosphinx – The Hawk-Headed Sphinx and Form of Horus the Elder

The hieracosphinx is a mythical creature located in both Egyptian sculpture and European heraldry. It was a common representation of the god Haroeris, also known as “Horus the Elder.” The term “Hieracosphinx” originates from the Greek words which combine Hawk and Sphinx. The Hieracosphinx is described as featuring the body of a lion and the head of a hawk. The name was invented and coined by the Greek historian Herodotus for the hawk-headed sphinx, which distinguished them from the ram-headed sphinx, which he referred to as the Criosphinx.

Medjed – The Sacred Elephantfish of Osiris’ Myth

Medjed was a type of elephantfish revered in the rich ancient Egyptian religion and particularly venerated in the region of Oxyrhynchus. Within the Osiris Myth, held that these fish consumed the severed genitalia of the god Osiris, who had been dismembered and scattered by his evil brother Set, according to the myth of Isis and Osiris. The settlement of Per-Medjed in Upper Egypt took its name from these creatures.

They are now more commonly recognized by their Greek designation, Oxyrhynchus, which means “sharp-nosed,” which corresponds to the Egyptian portrayal of the fish. In their role as sacred animals, they often appear adorned with horned sun discs. Certain figurines even include loops for wearing them as pendant amulets. The freshwater elephant fish, which are one of the subfamilies of Mormyrinae that are sizable inhabitants of the Nile’s freshwater, are characterized by their unique downturned snouts.

The depiction of the Oxyrhynchus fish, featuring wall paintings, bronze figurines, or wooden coffins shaped like fish with downturned snouts and horned sun-disc crowns reminiscent of those worn by the goddess Hathor of joy and pleasure, bears a resemblance to members of the Mormyrus genus.

Serpopard – The Serpent-Leopard Hybrid of Chaos

The serpopard is a mythical creature found in ancient Egyptian and Mesopotamian art (3500–3000 BC), characterized by its combination of a leopard’s body and a serpent’s long neck and head, which was dubbed the harbinger of Chaos. The term “serpopard” is a modern creation, blending “serpent” and “leopard,” which makes it one of the most unique mythological creatures that is depicted on cosmetic palettes from Predynastic Egypt and cylinder seals from Mesopotamia, often with intertwined necks.

In Egyptian art, it may symbolize chaos beyond Egypt’s borders, subdued by the king, while in Mesopotamian art, they are portrayed in pairs, reflecting natural vitality. The creature’s appearance leans more towards a long-necked lioness rather than a serpent, with no serpent-specific features. The exaggerated necks may serve artistic purposes. Lionesses, significant in Egyptian religion, likely represented protection and royalty. Similar fantastical creatures appear in other cultures, too.

Babi – The Bloodthirsty Baboon God of the Afterlife

Babi was a mythical ancient Egyptian creature that exhibited attributes of evil demonic deities. Many scholars view Babi, meaning chief of the baboons,” “bull of the baboon,” as a glorification of the Hamadryas baboon during Ancient Egyptian civilization. Ancient Egyptians perceived baboons as violent and aggressive creatures, leading to Babi’s portrayal as a bloodthirsty creation feasting on the organs and entrails of the dead.

Similar to Ammit, some texts depict Babi by fiery lakes, consuming the sinful souls of the departed. Symbolically, baboons’ notable high libidos associated Babi with virility for the deceased. This connection led to phallic symbolism in an ancient funerary text spell, ensuring the enjoyment of a relationship in the afterlife. Babi’s distinct attributes linked him to the chaotic forces of Set, an occasionally adversarial Egyptian god.

Set Animal (Sha) – The Totemic Beast of Chaos and Storms

The Set animal, also known as the sha, was a totemic creature associated with the ancient Egyptian god Set of chaos and evil. It is often referred to as the Typhonian animal due to its connection with the Greek monster Typhon. While not recognizable as any specific real animal, it held significant symbolism in ancient Egyptian culture and religion. Scholars believe it existed solely in the realm of Egyptian imagination and was not an actual creature. The Set animal is depicted as a slender canid resembling a greyhound or jackal.

It has distinctive features, including a stiff, often forked tail that stands upright or at an angle, erect square or triangular ears, and a long nose with a slight downward curve. Its color is typically black, though it may also be reddish. Depictions of the Set animal appear in Egyptian art from Naqada III to the New Kingdom, spanning about two thousand years. It is found on various artifacts, including the Scorpion Macehead, serekhs of kings like Seth-Peribsen and Khasekhemwy, and even in royal cartouches of later pharaohs.

The god Set himself was often portrayed with a head resembling the Set animal, and the sha’s features were used in hieroglyphs to represent concepts related to chaos, violence, and storms. The Set animal’s exact identity has been the subject of debate, with various proposals ranging from a jackal or Saluki (a domesticated dog breed) to more speculative suggestions like an African wild dog, pig, antelope, giraffe, donkey, fennec fox, long, round snout, or aardvark.

Some believe the set animal represented a giraffe, but the scholars believed to had differentiated between the hybrid creature and giraffes. Over time, Set’s reputation diminished, especially with the rise of the Osiris cult, and depictions of the Set animal became less common, which is a sign of the eternal victory of good over evil. The sha’s association with Set, as well as its unique characteristics, makes it a distinctive and intriguing symbol in ancient Egyptian art and culture.

Khepri – The Scarab God of the Rising Sun and Transformation

Associated with the scarab beetle, also known as the dung beetle, Khepri stood as a unique figure within Egyptian mythology. Portrayed typically as a human body with the head of a beetle in ancient Egyptian funerary scrolls, Khepri’s veneration carried a symbolic essence, representing the divine forces steering the sun’s celestial journey across the heavens.

This link stemmed from the scarab beetle’s behavior of rolling balls of dung across the arid desert landscape. From within these dung balls, young beetles emerged, hatching from eggs laid by their progenitors. This phenomenon is intertwined with the Egyptian term “kheper,” conveying concepts of transformation and creation.

Furthermore, Khepri assumed a subordinate role in comparison to the esteemed solar deity Ra, occasionally melding into Ra’s facets. Notably, Khepri personified the morning sun, while Ra emanated as the radiant midday sun. Fascinatingly, the ancient Egyptians also bestowed upon Khepri the status of a god of rebirth, considering beetles as entities that seemingly materialized from nothingness yet possessed the power to perpetuate their lineage.

Ouroboros – The Eternal Serpent of Rebirth and Cosmic Cycles

The ouroboros is a very famous ancient symbol that portrays a creature of a serpent or dragon eating its tail. It has roots in Egyptian and Greek traditions, later becoming a symbol in Gnosticism, Hermeticism, and alchemy. In some instances, certain snakes, like rat snakes, have been observed attempting to consume themselves.

The term “ouroboros” comes from Greek words for “tail” and “eating.” This symbol is often interpreted as representing eternal renewal, the cycle of life, death, and rebirth, with the shedding of the snake’s skin representing the transmigration of souls. It also holds fertility symbolism in certain religions, with the tail as a phallic symbol and the mouth as a womb-like symbol.

In ancient Egypt, the ouroboros motif appears in the Enigmatic Book of the Netherworld, a funerary text in Tutankhamun’s tomb. It depicts a serpent encircling a figure’s head and feet, representing the cyclical nature of time and periodic renewal. The symbol is associated with disorder surrounding the orderly world and persisted through Egyptian and Roman times, often found on magical talismans. The Latin commentator Servius recognized its Egyptian origins and noted its representation of the cyclical nature of the year.

Sphinx – The Divine Guardian of Wisdom and Royal Tombs

The Sphinx, the teller of stories and the spreader of dreams, is often linked with ancient Egypt, but is more of a symbolic representation than an individual mythical creature in Egyptian belief. It has been found in various cultures beyond Egypt, including Turkey and Greece. Egyptian Sphinxes had a lion’s body and a human, falcon, or ram head, symbolizing protection for sanctuaries and pyramids and representing both the Pharaoh and Ra’s divine power.

In contrast, Greek Sphinxes, offspring of the serpent Typhon, are usually seen as treasure-guarding monsters, differing from their Egyptian counterparts with wings and snake-like tails. All sphinxes share the common role of guarding treasures or wisdom and challenging travelers with riddles before allowing passage.

The Sphinx of Giza’s construction date is uncertain, but it’s believed to resemble Pharaoh Khafre and dates back to around 2600-2500 BC. Some claim it’s older due to water erosion evidence, but this idea lacks support. Other sphinxes include those with pharaoh heads, such as Hatshepsut’s granite likeness now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the alabaster Sphinx of Memphis.

Sphinxes of Egypt were guardians, often associated with sun deities like Sekhmet. They lined avenues and stairs at temples and tombs, symbolizing protection. The Great Sphinx is an iconic emblem of Egypt, appearing on stamps, coins, and official documents. In 2023, a limestone sphinx resembling Roman Emperor Claudius was discovered at Dendera Temple Complex.

Uraeus – The Rearing Cobra of Royal Protection and Power

The Uraeus, also known as the Ouraeus, means the rearing cobra, which is a stylized representation of an Egyptian cobra, symbolizing sovereignty, deity, and divine authority in ancient Egypt. It is associated with the goddess Wadjet, often depicted as a cobra, who was a protector of Lower Egypt and the Nile River. The Uraeus was worn by pharaohs either as a head ornament with Wadjet’s body atop their heads or as a crown encircling their heads, signifying protection and reinforcing their authority, which explains why it was seen with the majority of ancient Egyptian Pharaohs encircling their Pschent or Double Crown.

The Uraeus played a role in the crowns worn by pharaohs and was an important emblem during the unification of Egypt around 3200 BC by Menes or Narmer, representing both Wadjet and Nekhbet, patron goddesses of different regions. As Egypt’s pharaohs were seen as manifestations of the sun god Ra, the Uraeus was believed to spit fire on enemies from the goddess’s fiery eye, further protecting the rulers. The Golden Uraeus of Senusret II, made of solid gold with intricate gemstone inlays, is one of the most notable examples.

The Uraeus was also used as a hieroglyph and adorned various artifacts, including statuary, jewelry, and buildings. In Egyptian art, the Uraeus was sometimes depicted as part of the Blue Crown worn by pharaohs, particularly in combat scenes, emphasizing its protective role. The concept of the Uraeus may have influenced the depiction of seraphim in later Abrahamic religious traditions.