Summary

- Ancient Egyptian masks played a pivotal role in life, death, and spirituality, symbolizing protection, transformation, and rebirth. Worn by both the living and the deceased, masks connected individuals to divine powers.

- Gold masks, like Tutankhamun’s, represented immortality and divine status, while cartonnage masks were commonly used to preserve identity in the afterlife.

- Priests used deity masks during rituals to invoke and channel divine energy.

- These masks, crafted with artistic precision using materials like gold, silver, and precious stones, served as tools for ensuring eternal life and maintaining cosmic harmony.

- Beyond their spiritual significance, masks also reinforced social and political hierarchies, representing authority and divine favor in public ceremonies.

Ancient Egyptian masks are profound symbols of a civilization deeply connected to the spiritual and divine. Worn both in life and death, these masks served as transformative tools, allowing individuals to bridge the mortal and celestial realms. Whether crafted from gold to adorn a pharaoh’s tomb, painted onto cartonnage for noble burials, or used in rituals by priests channeling the power of gods, masks embodied protection, rebirth, and immortality.

The artistry and symbolism of these masks reveal a rich tapestry of beliefs about the soul, identity, and afterlife. They protected the deceased on their journey through the underworld, ensured recognition by divine beings, and reflected the wearer’s transformation into an eternal, god-like entity. This article explores the fascinating roles of masks in Ancient Egypt and the ritualistic, funerary, and social aspects of one of history’s most captivating civilizations.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

This information does not seek to degrade or insult any religion. All the information is based on historical evidence, any similarities that you may find with your own faith or religion are from the figment of your imagination.

The Spiritual Significance & Symbolism of Ancient Egyptian Masks

Ancient Egyptian masks were deeply intertwined with spiritual beliefs, serving as powerful Ancient Egyptian Symbols of protection, transformation, and rebirth. In funerary practices, masks ensured the soul (ka) could recognize its physical body, a crucial step for navigating the underworld and achieving eternal life in the Field of Reeds, the Egyptian equivalent of paradise. They also provided a divine visage for the deceased, aligning them with the gods and enabling their acceptance into the Egyptian Afterlife’s divine council.

Masks were not limited to the dead; they held significant roles in the lives of the living. Priests, priestesses, and magicians wore masks during religious rituals to embody Ancient Egyptian Deities like Anubis, Hathor, or Bes. These masks allowed the wearer to channel divine authority, granting them the spiritual power necessary to perform rituals and protect the community. For example, Anubis masks, featuring jackal heads, were crucial in mummification ceremonies, signifying Anubis’s role as guardian and guide of the dead.

Masks reinforced the Egyptian worldview that the mortal and divine realms were deeply interconnected. Whether aiding the living by invoking divine assistance or ensuring the deceased’s safe passage to the afterlife, masks symbolize the seamless movement between human and spiritual existence.

Gold and Glory: The Role of Gold Masks in Ancient Egyptian Funerary Practices

Gold masks epitomized Ancient Egypt’s beliefs in immortality and divinity. Gold, associated with the flesh of the gods, was considered to have eternal, imperishable, and luminous qualities essential for the transformation of the deceased into a divine being.

The most famous example, the mask of Tutankhamun, crafted in 1323 BCE, weighs over 10 kilograms and features inlays of lapis lazuli, carnelian, quartz, and turquoise. Its inscriptions, taken from the Book of the Dead, invoked protective spells to guard the young king’s journey through the afterlife. The mask’s nemes headdress and symbols of the cobra and vulture represented the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, further emphasizing Tutankhamun’s divine authority even in death.

While gold masks were predominantly used by pharaohs, they were not exclusive to royalty. Wealthy nobles during the New Kingdom and the Third Intermediate Period also adorned themselves with gilded masks, aspiring to eternal life alongside the gods. These masks often featured protective deities, inscriptions, and cosmic motifs symbolizing regeneration and divine favor.

Gold’s reflective brilliance linked it to the sun god Ra, central to Egyptian theology. This association with Ra reinforced the deceased’s eternal life and their role in maintaining cosmic order (Ma’at). By combining artistry with profound symbolism, gold masks not only protected the deceased but also elevated them to a divine status that would last for eternity.

Mummification and Masks: Preserving Identity in the Afterlife

The Ancient Egyptian Practice of Mummification sought to preserve the body as a home for the soul in the afterlife. Masks were a vital part of this process, particularly in protecting and preserving the head, considered the seat of identity and spirit.

Old Kingdom Beginnings: During the Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BCE), plaster-coated linen masks were used to cover the face of the deceased. These masks were simple but ensured that the ba (personality) and ka could reunite with the body.

Middle and New Kingdom Advances: By the Middle Kingdom (c. 2040–1782 BCE), cartonnage masks—made from layered linen or papyrus stiffened with plaster—became prevalent. These masks were intricately painted with features symbolizing divine perfection. In the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BCE), masks became more elaborate, incorporating protective spells and celestial imagery.

21st Dynasty Innovations: The silver and gold mask of Psusennes I (c. 1077–943 BCE) exemplifies the pinnacle of funerary mask craftsmanship. These masks provided not just physical protection but also spiritual transformation, ensuring the deceased’s identity was preserved and recognized by the gods.

Masks often featured inscriptions, including spells from the Book of the Dead, and symbols of protection, like the Eye of Horus. These elements highlighted the belief that preserving one’s physical and spiritual identity was essential for achieving eternal life.

The Art and Craftsmanship of Ancient Egyptian Masks

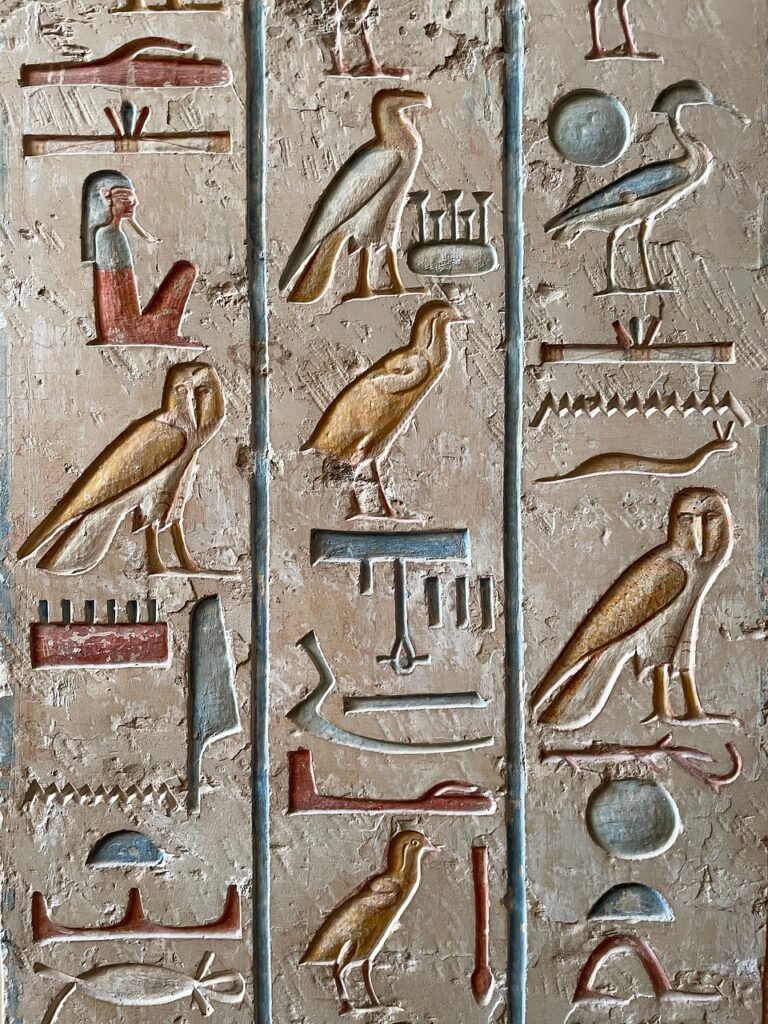

The creation of Egyptian masks combined technical skill with profound artistry from the Ancient Egyptian Craftsmen. Early masks from the Old Kingdom were made from wood or painted plaster, while later periods saw the evolution of cartonnage masks and, for the elite, masks crafted from gold and silver.

The Various Materials of Ancient Egyptian Masks:

- Cartonnage: A blend of linen or papyrus stiffened with plaster, often painted or gilded.

- Wood: Used in early masks and shaped to match the deceased’s face.

- Gold and Silver: Reserved for royalty and high-status individuals, symbolizing immortality and divine nature.

- Semi-Precious Stones: Inlaid in masks to enhance their cosmic and regenerative symbolism.

The Incredible Techniques of Ancient Egyptian Masks:

- Gilding and Painting: Masks were adorned with bright colors and gold leaf to reflect divine qualities.

- Molding: Early masks were molded directly onto the deceased’s face or on a wooden core.

- Inlay Work: Artisans used lapis lazuli, turquoise, and carnelian to add intricate details, representing celestial and earthly power.

The designs were both aesthetic and functional. Features like wide eyes symbolized vigilance, while idealized expressions embodied divine harmony. Masks not only preserved the deceased’s visage but also transformed them into god-like beings, ensuring their acceptance in the afterlife.

By the Greco-Roman period (332 BCE–395 CE), masks became highly stylized and often included floral and geometric motifs. These masks were sometimes part of a full-body cartonnage set, emphasizing protection and divine alignment.

The Mask of Tutankhamun: A Glimpse into the Life of an Ancient Egyptian Pharaoh

Discovered in 1922 by Howard Carter, the mask of Tutankhamun (1323 BCE) is one of the most celebrated artifacts of Ancient Egypt. It epitomizes the grandeur of the 18th Dynasty and provides insights into the religious and cultural beliefs of the period.

Weighing over 10 kilograms, the mask is crafted from gold and adorned with inlays of lapis lazuli, carnelian, quartz, and obsidian. Its Nemes headdress is topped with a cobra and vulture, symbolizing the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt. The false beard represents the pharaoh’s divine status.

The mask’s inscriptions include protective spells, ensuring the young king’s safe passage to the afterlife. Its craftsmanship reflects the advanced metallurgical and artistic skills of the time, offering a glimpse into the sophistication of Ancient Egyptian artisans.

Masks and Gods: How Deities Were Represented in Ancient Egyptian Masks

Masks in Ancient Egypt were profound embodiments of divine power, created to bridge the human and spiritual realms during rituals and ceremonies. By wearing masks of gods, priests, magicians, and performers symbolically assumed divine identities, channeling the deities’ powers.

Anubis Masks: Essential in mummification rituals, Anubis masks symbolized the jackal-headed god of embalming and the afterlife. Anubis’s role in protecting the dead was central to Egyptian funerary practices. These masks helped officiants align themselves with the deity’s divine authority, ensuring proper rites were observed to guide the deceased through the underworld.

Lion-Headed Masks: Representing Sekhmet, these masks were used in rituals of healing and destruction. Sekhmet, the goddess of war and medicine, embodied dual powers—capable of both devastation and restoration. Rituals wearing Sekhmet masks often focused on invoking her protective and curative aspects, especially during plagues or natural disasters.

Masks of Bes and Hathor: Bes, the dwarf god associated with fertility, music, and domestic protection, was often depicted in masks used during household rituals. Hathor masks represented love, joy, and fertility. Both deities’ masks were frequently worn during festivals, emphasizing their connection to life’s celebratory and nurturing aspects.

Symbolism and Ritual Use: Each mask’s design and materials enhanced its divine resonance. Jackal heads, lion faces, or depictions of Bes’s jovial expression were more than artistic choices—they were spiritual tools for invoking the gods’ presence. During temple rituals, priests wearing these masks reinforced the gods’ active participation in maintaining cosmic order (Ma’at).

Masks as Social and Political Symbols in Ancient Egypt

In addition to their spiritual roles, masks symbolized authority and hierarchy in Ancient Egyptian society. They were deeply intertwined with the power structures of the state and its religious ideology.

Royal Masks: The pharaoh, regarded as a living deity, often donned symbolic regalia, including masks or headdresses, during significant rituals. These items reinforced their divine status and their role as intermediaries between gods and humans. The nemes headdress or depictions like the funerary mask of Tutankhamun demonstrated their eternal connection to the divine.

Noble Masks: High-ranking officials, priests, and nobles also utilized masks to reflect their societal status. While these masks were less ornate than royal ones, they often incorporated gold leaf, vibrant colors, or symbolic motifs. They conveyed not only wealth but also proximity to divine favor.

Public Ceremonies and Festivals: During large-scale events, masks representing deities were paraded to visually affirm the pharaoh’s alignment with divine powers. These processions strengthened the connection between the state, religion, and people, ensuring loyalty and cultural unity.

Funerary Masks: A Symbol of the Pharaoh’s Eternal Power

Funerary masks served as an enduring testament to the divine and eternal nature of the deceased, especially Pharaohs. These masks symbolized the ruler’s transformation into a god after death, ensuring they maintained authority even in the afterlife.

Tutankhamun’s Mask: Crafted in 1323 BCE, Tutankhamun’s golden mask is a perfect example of a funerary mask’s role. The cobra and vulture on the headdress symbolized protection from Wadjet and Nekhbet, guardians of Upper and Lower Egypt. Inscriptions from the Book of the Dead were etched into the mask, ensuring the young king’s safe journey to eternity.

The New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period Innovations: Funerary masks during these eras grew increasingly ornate, with gilding, inlaid stones, and intricate detailing. These masks were not merely artistic creations but divine tools designed to guide and protect the deceased in the afterlife.

Eternal Power: By presenting the deceased in an idealized, god-like form, masks reinforced the pharaoh’s role as a cosmic ruler, maintaining balance (Ma’at) in both the mortal and spiritual realms.

The Use of Masks Beyond Royalty in Ancient Egypt

While masks for royals were lavish, masks also served non-royals in funerary and ritual contexts. Their materials and craftsmanship varied based on the individual’s social status.

Cartonnage Masks for the Elite: Wealthy Egyptians used cartonnage masks, crafted from layers of papyrus or linen stiffened with plaster, painted with symbolic motifs, and adorned with vibrant pigments. These masks highlighted the individual’s spiritual aspirations and societal standing.

Middle-Class and Commoner Use: During the Greco-Roman period (332 BCE–395 CE), masks became more widespread due to cheaper production methods. Terra-cotta and clay masks allowed the middle class to participate in funerary traditions once reserved for the elite.

Everyday Rituals: Masks like the Bes mask from Kahun show their use beyond death. Used in household ceremonies, they invoked divine blessings for fertility, protection, and health, illustrating the democratization of mask usage in Egyptian spirituality.