Summary

- The Egyptian nobility was crucial to the functioning of ancient Egypt, bridging the gap between the Pharaoh and the people.

- They were responsible for managing taxes, overseeing agricultural production, defending Egypt’s borders, and leading cultural and religious endeavors.

- The hierarchy within the noble class, included the powerful viziers, regional governors (nomarchs), high priests, military commanders, and even noblewomen.

- The wealth and power of the nobility stemmed from land ownership, military prowess, and their involvement in religious and artistic projects.

- Their legacy is seen in the grand tombs, temples, and monuments they commissioned, which continue to stand as a testament to their influence on Egyptian civilization.

The Egyptian nobles were the architects of the kingdom’s success, bridging the gap between the ruling Pharaoh and the general populace. As administrators, priests, military commanders, and patrons of art and culture, they wielded significant power and influence, shaping the political, social, and religious landscape of one of history’s most remarkable civilizations.

From their luxurious lifestyles and vast estates to their spiritual responsibilities as guardians of temples and patrons of the gods, the nobles left an indelible mark on Egypt’s legacy. By examining their hierarchy, contributions to governance, and cultural impact, we can better understand the profound importance of these elites in maintaining the kingdom’s stability and prosperity through the ages.

The Role and Power of Nobles in Ancient Egypt

In ancient Egypt, nobles served as the administration’s backbone, acting as intermediaries between the Pharaoh and the people. Their responsibilities included collecting taxes, managing agricultural production, overseeing infrastructure projects like canals and irrigation systems, and ensuring that local regions complied with royal policies.

During the Old Kingdom of Ancient Egypt (c. 2686–2181 BCE), nobles operated under the Pharaoh’s direct supervision, but by the Middle Kingdom of Ancient Egypt (c. 2055–1650 BCE), they gained greater autonomy due to the decentralization of power. This autonomy allowed them to amass wealth and influence, but it also contributed to periods of instability, such as during the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BCE).

Nobles were also tasked with supervising the military, serving as commanders in campaigns or as governors responsible for defending Egypt’s borders. They organized labor forces for large-scale construction projects, including pyramids and temples, ensuring the Pharaoh’s grand architectural vision was realized. Their power extended into the judicial realm, where they acted as judges in local disputes, reinforcing both civil and religious law.

Hierarchy Among the Nobility: Understanding Ancient Egypt’s Elite Class

The noble class of ancient Egypt was a cornerstone of its civilization, functioning within a highly structured hierarchy. Each rank within the nobility carried specific duties that contributed to the kingdom’s stability, efficiency, and cultural legacy. Their influence extended across political, religious, and military domains, making them indispensable to the Pharaoh’s rule.

The Vizier: The Pharaoh’s Right Hand

The vizier was the most powerful figure in Egypt after the Pharaoh, responsible for the smooth functioning of the state. Often likened to a prime minister, the vizier managed an extensive portfolio:

- Administrative Oversight: The vizier supervised all departments, including agriculture, taxation, and construction. They ensured the surplus from Egypt’s bountiful harvests was stored and distributed efficiently.

- Judicial Authority: Acting as the chief judge, the vizier presided over legal disputes and ensured laws were uniformly enforced. Records from the Middle Kingdom describe the vizier as the “Keeper of Ma’at,” responsible for maintaining order and justice.

- Monumental Projects: Viziers played key roles in overseeing massive construction projects, such as pyramids and temples. For instance, Imhotep, vizier to Pharaoh Djoser, designed the Step Pyramid at Saqqara—an architectural marvel that laid the foundation for later pyramid designs.

Notable viziers included Rekhmire, who served under Thutmose III during the 18th Dynasty. His tomb inscriptions provide detailed accounts of his administrative duties and diplomatic interactions.

Nomarchs: Guardians of the Nomes

The nomarchs, or regional governors, managed Egypt’s 42 nomes (administrative regions). Their responsibilities included:

- Economic Management: Nomarchs ensured that taxes were collected in the form of grain, livestock, and goods, which were then sent to the central government.

- Military Defense: They organized regional militias to defend against foreign invasions and internal unrest.

- Cultural Patronage: Nomarchs often funded local religious festivals and the construction of temples within their regions.

During periods of strong central authority, such as the Middle Kingdom, nomarchs were carefully monitored. However, during times of political weakness, like the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BCE), they became semi-autonomous, leading to regional rivalries and fragmentation.

High Priests: Stewards of the Divine

The high priests, particularly those of Amun, held enormous power, especially during the New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt. Their responsibilities extended far beyond religious rituals:

- Economic Influence: The temples of Amun at Karnak and Luxor controlled vast estates, agricultural lands, and a significant labor force. The wealth of these temples rivaled that of the Pharaoh.

- Political Power: High priests often acted as advisors to the Pharaoh and wielded considerable influence over state decisions. By the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1070–664 BCE), some high priests of Amun essentially ruled Upper Egypt as semi-independent leaders.

Notable high priests of ancient Egypt, such as Herihor, demonstrated how the position could become a stepping stone to political dominance.

Military Commanders: Defenders of Egypt

Nobles frequently served as military leaders, commanding troops in campaigns and defending Egypt’s borders. Their military contributions included:

- Territorial Expansion: During the New Kingdom, noble generals led conquests in Nubia and the Levant, securing resources like gold and timber.

- Fortifications: Nobles oversaw the construction and maintenance of strategic fortresses, such as Buhen and Semna, along the Nubian frontier, safeguarding Egypt’s southern borders.

- Diplomatic Strategy: Nobles often conducted negotiations during conflicts, as seen during the Battle of Kadesh (c. 1274 BCE) when generals worked alongside Pharaoh Ramesses II to outmaneuver the Hittites.

Military achievements elevated the social status of noble commanders, ensuring their legacy through inscriptions and monuments.

Noble Women in Ancient Egypt: Influence and Authority

While ancient Egyptian society was patriarchal, women in ancient Egypt, especially noblewomen, wielded significant influence within their households, the court, and religious institutions. Their roles included:

- Estate Management: Noblewomen managed large estates, supervising workers and ensuring the smooth operation of agricultural production.

- Religious Leadership: As priestesses, many noblewomen participated in temple rituals. Titles such as God’s Wife of Amun granted them political and economic power, with access to temple wealth and influence over temple activities.

Prominent noblewomen/queens include:

- Hatshepsut: As one of Egypt’s most successful Pharaohs, Hatshepsut legitimized her rule through monumental projects such as her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri.

- Nefertiti: Renowned for her beauty and political acumen, Nefertiti co-ruled alongside Akhenaten, advocating for the worship of Aten during the revolutionary Amarna Period.

Wealth, Land, and Inheritance: Pillars of Noble Prosperity

The wealth of the nobility was rooted in land ownership, often granted by the Pharaoh in recognition of service. Key aspects of their wealth included:

- Agricultural Production: Estates were self-sufficient, producing food, wine, and textiles. Surpluses were taxed and used to support the state or traded for luxury goods.

- Inheritance Practices: Land and wealth were passed down through generations, ensuring the continuity of noble families. Marriages among elites often reinforced alliances and expanded family wealth.

- Material Culture: Noble estates were adorned with lavish furnishings, fine jewelry, and artistic decorations. Their tombs reflected their status, featuring elaborate carvings, gold, and depictions of their wealth.

The Wilbour Papyrus, a Middle Kingdom document, highlights the complexity of land ownership and taxation, emphasizing the role of the nobility in Egypt’s economy.

Nobles and Religion: Guardians of Egypt’s Spiritual Life

Religion was central to noble life, and they served as key patrons of temples and rituals. Their contributions included:

- Temple Construction: Nobles funded the construction of shrines, pylons, and obelisks, ensuring their legacy was intertwined with the gods they worshiped.

- Religious Intermediaries: As priests and temple overseers, nobles mediated between the gods and the Pharaoh, reinforcing the divine order of Ma’at.

- Afterlife Preparations: Elaborate tombs and chapels ensured that nobles were venerated after death. Inscriptions often appealed to the living for offerings to sustain their spirits in the afterlife.

The nobility’s role as guardians of Egypt’s spiritual life solidified their influence and ensured their memory endured in both religious and secular contexts.

The Influence of Nobles on Ancient Egyptian Art and Architecture

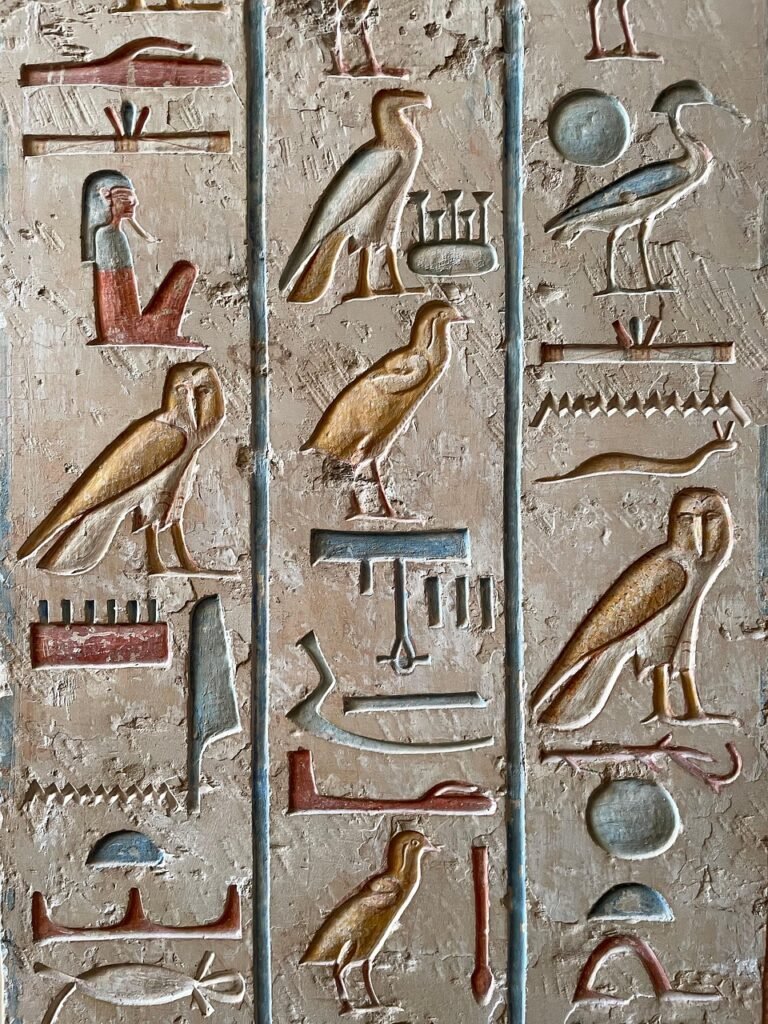

The artistic and architectural legacy of the Egyptian nobility is unparalleled, as their wealth and status allowed them to commission works that symbolized their power, piety, and aspirations for immortality. Tombs of the nobles were not only places of burial but also celebrations of life and the afterlife.

These masterpieces of Ancient Egyptian Art were adorned with intricate reliefs and vibrant paintings depicting banquets, hunting scenes, agricultural activities, and religious ceremonies, offering invaluable insights into ancient Egyptian life and beliefs. For instance, the Tomb of Rekhmire in Thebes vividly portrays foreign delegations bringing tribute, a testament to Egypt’s extensive diplomatic and economic ties under Thutmose III’s rule.

The Valley of the Nobles near Luxor contains over 400 tombs of elite officials, each tailored to the individual’s achievements and beliefs. The Tomb of Ramose, a vizier during the reign of Amenhotep III and Akhenaten, showcases a unique transition in art styles, blending the traditional with the Amarna period’s distinctive realism.

Nobles also played a critical role in the construction and decoration of temples. They financed monumental temples such as the Temple of Karnak and Luxor Temple, contributing to expansions and adding chapels or pylons. Their patronage ensured the creation of colossal statues, obelisks, and reliefs depicting religious festivals. This collaboration between the nobles and skilled artisans elevated Egyptian art to its zenith.

Architectural innovations, such as rock-cut tombs during the Middle and New Kingdoms, reflected the elite’s emphasis on permanence and security in the afterlife. Nobles used their influence to commission false doors, serdabs (statues chambers), and hieroglyphic inscriptions, ensuring that their legacy would endure for eternity.

The Nobility and the Pharaoh: Relationship Dynamics

The interplay between the Pharaoh and the nobility was essential to Egypt’s stability. Nobles supported the Pharaoh’s rule by managing regional governance, providing military support, and financing religious and construction projects. In return, the Pharaoh granted them titles, privileges, and landholdings.

Periods of central authority, such as the Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BCE), saw a tightly controlled relationship, with nobles acting as loyal agents of the Pharaoh. However, during times of weakened central power, such as the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BCE), nobles in the provinces (nomarchs) began asserting their independence. This decentralization often led to internal strife and political fragmentation.

To counteract this, Pharaohs like Amenemhat I during the Middle Kingdom introduced reforms to diminish noble autonomy. He centralized the military, relocated the capital to Itjtawy, and replaced hereditary governors with appointed officials, ensuring loyalty to the throne.

Despite occasional power struggles, the nobility and Pharaohs shared a mutually beneficial relationship. For example, Thutmose III (r. 1479–1425 BCE) relied on his generals and administrators to maintain Egypt’s empire, while Ramesses II (r. 1279–1213 BCE) collaborated with nobles to achieve his architectural ambitions.

The Military Role of the Nobles in Ancient Egypt

The Egyptian nobility played an indispensable role in the military, serving as commanders of armies and defenders of the kingdom. They led campaigns that expanded Egypt’s territory during the New Kingdom, securing control over Nubia and the Levant. Military achievements were often commemorated in inscriptions and monuments, immortalizing their contributions.

Fortresses like Buhen, established during the Middle Kingdom near the Nubian border, were overseen by nobles who managed garrisons and controlled trade routes. Nobles also participated in constructing strategic outposts along the Sinai Peninsula, protecting mining operations and ensuring the safety of Egyptian workers.

During major conflicts, such as the Battle of Kadesh (c. 1274 BCE) between Egypt and the Hittites, noble generals played crucial roles in planning and executing military strategies. Their expertise and loyalty were essential to maintaining Egypt’s security and influence.

Education and Culture: How Nobles Shaped Egypt’s Intellectual Landscape

The nobles’ patronage of education and the arts fostered a rich intellectual and cultural heritage. They established and supported scribal schools, where young elites learned mathematics, hieroglyphics, and administration. These schools produced the bureaucrats and record-keepers who maintained Ancient Egypt’s Economy and governance.

Nobles were also patrons of literature, commissioning works that reflected ethical teachings, administrative wisdom, and religious devotion. Ancient Egyptian texts like The Instructions of Ptahhotep (c. 2400 BCE) and The Story of Sinuhe were preserved through the efforts of noble scribes. These writings provided moral and practical guidance for governing and living a virtuous life.

In addition to literature, nobles funded advancements in astronomy, medicine, and architecture, ensuring that Egypt remained a beacon of innovation in the ancient world. They also supported artists and craftsmen, commissioning sculptures, jewelry, and ceremonial objects that highlighted their refined tastes and religious devotion.

The Decline of the Nobility: Changing Roles and Power Shifts in Ancient Egypt

The influence of the nobility waned during the Late Period (c. 664–332 BCE) as foreign powers increasingly dominated Egypt. The centralization of authority under the Persians and later the Ptolemies replaced the traditional noble class with foreign administrators and military governors. Native Egyptian nobles retained some religious roles but lost much of their political and economic power.

During the Ptolemaic Period (305–30 BCE), the integration of Greek practices further marginalized Egyptian elites. Temples remained significant centers of power for noble priests, but their autonomy was curtailed by royal and foreign oversight.

Despite this decline, the legacy of the nobility endured through their tombs, inscriptions, and contributions to Egypt’s culture. Their patronage of art, literature, and religion ensured that the grandeur of ancient Egypt continued to inspire civilizations for millennia.